“Oh no, not here, too.” My gut wrenched and lunch threatened to erupt from within. My wife and I were on an afternoon hunt in an area we had visited for a decade. Many local families had hunted here for four, even five, generations. We had just rounded a bend on a rutted, muddy track the county laughingly called a “road” which is a wonderful vantage point to see game on the distant hill sides. Once you spot them, dismount and make a challenging stalk to get close enough for a shot. I brought the intrepid little Jeep, our constant companion on hunting adventures for almost twenty years, to a halt. Bad news screamed at us from three sides.

Posted! Private Property. No Trespassing or Hunting Under Penalty of Law.

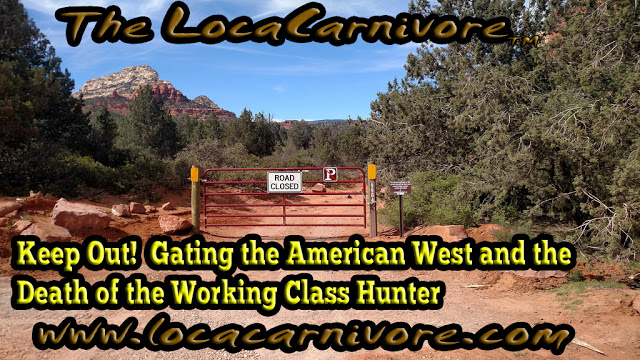

Lurid yellow signs loomed over us and bracketed a shiny new ranch-style gate which blocked the county road. We just stared for a moment, gut-punched. There had been no “For Sale” signs in the area–ever. Yes, we knew some small private lots existed about a quarter-mile east from the road. Those had always been posted, but never gated, and public passage along the tributary roads had never been impeded. Live and let live. Until now.

The new gated and posted land had been, until just few months ago, one small part in an enormous tract which sprawled for thousands of acres across forested mountains and bubbling creeks. Land owned by an international timber company, who had “inherited” it from a U.S. Government grant to a railroad company in the 19th century. In short, they never paid a dime for it. It had been open to public use for over a hundred years. A profoundly simple and practical gentleman’s agreement existed between the company and the state: the company got the timber, and the public got near free rein on the numerous roads the company graded for access. A wonderful, mutually beneficial arrangement.

At least until the later 20th century. Market forces, combined with increasing regulation, for all intents and purposes killed the U.S. timber industry and the conglomerate in question had a dilemma on their hands. The land on which their trees sat had become more valuable that the timber itself. They spun off a subsidiary whose sole mission is to sell off the land.

Some has been either donated or sold to the state, more yet has been sold to The Nature Conservancy (more about them in a minute), and the rest has gone piecemeal to private parties. Some are developers and others wealthy individuals. At no point has the effect on the average resident hunter been seriously considered.

Song for the Workingman

In these parts, the average, everyday locacarnivore often works a blue-collar job, in many cases two or even three. Many work seasonal jobs. They are loggers, delivery truck drivers, store clerks, tradespeople, bar tenders (lots of bar tenders), ranch hands, or small business owners. In short, jobs are few, wages low, and people depend on the local forests and mountains to supplement their food supply. Hunting is no mere sport up here, it is serious business for feeding hungry families.

When we first moved here, we found a hunter’s paradise. At the time, tags were dirt cheap, and if you played things right, you could hunt something almost year round, and thanks to those timber companies you could get into remote areas by motor vehicle. A twenty-minute drive off the interstate could put you all alone in a rugged landscape surrounded by elk, deer, turkey, rabbit, grouse, moose, big horn sheep, even pronghorn. A busy working person could easily take a half-day here, a full day there, and get in a good, productive hunt. No need for horses laden with camp goods, or week-long backpack expeditions. You could hunt, and hunt well, on a shoestring budget in your spare time.

The New Religion

A seismic shift occurred in the 1990s and the years which followed. Government land managers at all levels; city, county, state, and federal, decided they hated the motor vehicle, and the hunters who depended on them.

National forests, once adorned with signs which read “Land of Many Uses” now sprout gates at every dirt road intersection. Often, just a main road through the forest remains open. Now, new signs announce, “Federal Property. Closed to Motor Vehicle Travel.” The land of many uses has become the land of many agendas.

Next, the state, in a well intended effort, declared it would absorb the timber company land now for sale and hold it in trust for “the people.” All well and good, except the state bureaucracy charged with managing the effort also hated motor vehicles. In fact, one employee responsible for documenting right of way has stated something to the effect hunters and their vehicles tear up the land and have no business being on state property. Not public land, “State Property.” The distinction speaks volumes. So, state land remains only accessible to physically fit, younger people who can trudge up and down mountains for ten miles with a hundred pound elk quarter on their back. Tough luck if you’re a disabled vet, agricultural accident victim, middle-aged and a bit rounder in the middle than you once were, or if you have an eight and a ten-year old child to ride herd over whom you want to teach to hunt.

When asked about this situation, anther state employee replied. “I don’t care. They can go to a food bank or get food stamps…I just follow instructions.” Where have we heard such words before? Hint, around 1945 at Nuremberg.

When asked about this situation, anther state employee replied. “I don’t care. They can go to a food bank or get food stamps…I just follow instructions.” Where have we heard such words before? Hint, around 1945 at Nuremberg.Nature Conservancy to the Rescue?

Amidst this undeclared war on the average hunter, the state announced it had heard the people loud and clear and would do “something.” The something became an initiative to transfer more timber company land to the state. The state had developed a financing scheme which would, they hoped, pay for all the land they wanted. Then their plans fell through after an unanticipated setback. They could not purchase everything they had their eye on. What to do now?

Over hill, with the sunrise behind them, rode the cavalry–The Nature Conservancy. They announced they would buy whatever land the state couldn’t afford, hold it in trust, and when the state got its shekels together, they’d sell it to the state (for a handsome profit it turned out). The state and TNC issued a joint communique in which TNC declared they would not alter the timber company policies when it came to public access. If you like your access, you can keep your access, so the line went.

The timber company lands passed to the TNC in due course and within days The Nature Conservancy erected gate after gate and sealed off “their” land to all motor vehicle access. Overnight, a small band of wealthy people in Santa Barbara, California disenfranchised almost a million people from any practical means to use the lands they had hunted on for a century or more. An all too familiar tale in the West, and echoes of the Soviet Union. “Yes, Comrade, you have rights, you just can’t use them.”

One area we used to hunt has a marvelous ridge complex which runs for miles. Before the TNC’s heavy-handed arrival, one could just motor up to one particular hill at dawn, dismount, and with a short, hundred foot climb, get onto the ridge where the elk hung out. Now, you must hike in from a gate for several miles before you can even think about climbing the ridge which means your hunt starts close to mid-day, not enough time. Oh, since overnight camping is prohibited, you can forget about setting up camp one day and hunting the next–assuming you have two days to spare and enough camping gear.

We used to pull a deer or two every season from this area, but since the gate went up, we’ve only managed one in the last six years. Tanks for nuttin’, as my Irish cousins would say.

When contacted at their office in this state, the TNC’s employee who administered the acquired land stated he hated motor vehicles and hunters, and his main concern was “reintroducing native grasses” along the old logging roads.

Years later, there are no native grasses, just acres of Russian nap weed, an invasive plant which kills native grasses. Seems the occasional vehicle traffic on those roads had suppressed the nap weed and now, without regular travel, the weed has exploded into a botanical plague upon the land. Well done Nature Conservancy, well done indeed. Love those “native grasses” you’ve put in.

A Grand Bargain

Over the last few years, fewer and fewer resident hunting licenses have been sold in this state. The game department has complained they no longer have sufficient revenue to accomplish their mission which is conservation and wildlife preservation. Survey after survey reveals local hunters are giving up on hunting for one primary reason–land access. While the state has tried to improve things, they’ve partnered with more large private land owners to allow hunters on their property and have knitted together the checkerboard hodgepodge state lands into unified wildlife management areas, they still don’t get it.

Over the last few years, fewer and fewer resident hunting licenses have been sold in this state. The game department has complained they no longer have sufficient revenue to accomplish their mission which is conservation and wildlife preservation. Survey after survey reveals local hunters are giving up on hunting for one primary reason–land access. While the state has tried to improve things, they’ve partnered with more large private land owners to allow hunters on their property and have knitted together the checkerboard hodgepodge state lands into unified wildlife management areas, they still don’t get it.When hunters here complain about no land access they mean, “We can’t drive where we used to, so we can’t get to backcountry trail heads for day hunts.” Unless you are a wealthy out-of-state hunter who can afford a guided week-long expedition, are wealthy enough to own horses, or are fit enough to hike miles and miles, your hunting options are now severely limited. The continued timber land selloff will not improve things.

So, what’s the solution? Is there one? Yes. There is a simple, elegant solution. During hunting season, allow people to access state and TNC land the way they once did, by motor vehicle. It is inconceivable vehicles will cause significant damage for four or five weeks each year. People drove on those lands year-round for almost a century. The mountains haven’t crumbled to dust and the animals haven’t gone extinct. Far from it, there are more game animals in the western U.S. now than at any other time in our history. The current policy is killing off hunting in this state and needs to change. Unless, or course, eliminating hunting is the ultimate goal. It certainly is the goal for many anti-hunting organizations which spend big money here each year to influence elections. ‘Nuff said there.

We need a grand bargain between those who manage public and non-governmental organization land and those who use it with respect. There are few drawbacks and much to gain if we reopen those lands to limited vehicle use. Let’s get the work-a-day hunters back where they belong; providing for their families and paying for necessary land and wildlife conservation.